Spider Webs

Everyone has seen a spider web, they are everywhere. Most of the time we pass them without thinking anything special. On some occasions when the weather conditions are just right, usually on dewy mornings, the world seems to be covered in spider webs. One such morning is shown in the photo below.

Of course what is going on in the view shown in this picture is that the dew is settling on the silk of the webs and making them visible. When they dry out, the webs are still there, just not as obvious. Here are two photos that demonstrate that effect. Here is the first shot, early in the morning when the dew is still obvious on the webs.

In the photo you can see a large number of small spider webs near the messy edge of our lawn. Here is the same view a few hours later after the humidity has dropped and the dew has evaporated from the webs.

Trust me, the webs are still there, just not visible. If you knelt down as I did the day I shot these photos, they were barely visible and still intact. I proved this by using a hand-held mister (one of those small plastic bottle misters you can buy in any pharmacy) to re-wet the webs. Voila… they re-appeared. Of course the spiders in those webs are counting on their invisibility, it is the secret to their success. The prey insects can’t see them as they crawl or fly along and they get tangled, becoming the next meal for the web spinning spider.

Four basic types of webs

For identification, one of the most useful things to notice about a spider is whether or not it was in a web, and what sort of web it was in. Spider students classify webs by their general structure into four basic kinds.

- orb webs – the classic round flat web

- funnel-shaped webs – webs that include an entrance to a funnel-shaped retreat

- sheet webs – simple or complex webs that include a flat or curved sheet

- space-filling or 3D webs – a tangle of silk lines filling an area of space

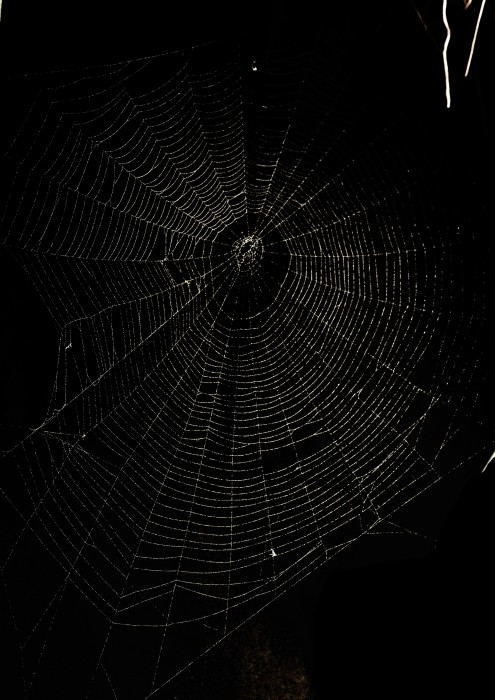

Orb webs–these are the iconic circular webs with a wheel-like appearance; composed of a central hub, radiating lines, and a concentric circular pattern. In actuality the circular part is actually one long spiral. Only this spiral is built of sticky silk with glue droplets. The remainder of the web, including the radial threads and the support frame are non-sticky. You can prove this to yourself the next time you encounter an orb web. Lightly touch one of the radial strands and then lift your finger away. Unless the web is wet with dew, it will release cleanly and quickly. In contrast when you try the same thing with a part of the sticky spiral, the entire web will stretch out as you withdraw your finger, you are stuck (don’t worry, it will release eventually!). Here is a photo of one such web:

Here is another, shot at night illuminated by a flash.

Here is an orb web photo with the resident spider, an arabesque orb weaver (Neoscona arabesca), still hanging in the center at the hub. She built the web the previous evening, now in the early morning the web is coated with dew and shows damage caused by the prey she captured during the night. Note the little blob below her, that is the undigestible remains from one of her prey.

An arabesque orbweaver (Neoscona arabesca) in her web on a dewy morning. The web was constructed the previous evening.

Many orb weaving spiders are nocturnal. Some continue to hunt at first light. Here is a big fat female shamrock orbweaver (Araneus trifolium) who has captured a fly in her web early in the morning.

One last orb web picture is below. It is of a banded garden spider (Argiope trifasciata) hanging in her web. You can’t really see much of the web except for an odd white zig-zag of thicker silk. This line is called the stabilimentum, here you can see two, one above her and a more prominent one below. There are many hypotheses for the function of stabilimenta such as these. The experimental evidence is somewhat equivocal. It seems clear that the presence can make the web more obvious to birds and prevents them from accidentally flying through the web. Insects may be attracted to the bright reflective line; or its brightness may make it harder for wasp predators to locate the spider. For some spiders their stabilimentum might even act as a sun shade at certain times of day. Whatever the true significance, the one hypothesis that has been soundly disproven is that it adds stability to the web (ironically the source of the original name).

Funnel-shaped webs–there are many common spiders in Ohio that build webs with funnel-shaped retreats. The most common are the grass spiders of the genus Agelenopsis. They emerge from their egg cases in the spring as tiny, unnoticeable, spiderlings. As they grow through the summer their webs become larger and more obvious. By late summer, many people notice them. One common place for webs is at the edges of lawns, hence the common name. Here is one example.

Another group of spiders common here in Ohio build webs with funnel-shaped retreats along rock walls and sometimes in fences. These five species in the genus Coras can be found throughout the year. The photo below illustrates one Coras web in an eroded sandstone rock face in the Hocking Hills.

Sheet webs–webs referred to as “sheet webs” are quite variable. The only feature in common is that the web includes a dominant sheet of silk. The sheet may be nearly flat, curved up into a dome or tent, or down into a bowl or “hammock” shape. Most of the spiders in Ohio that build conspicuous sheet webs are in the family Linyphiidae (sheetweavers and dwarf sheetweavers). Most members of this family of spiders are quite small, even as adults. Some of our most common species are included in this group. Below is the web of a “bowl-and-doily” spider. You can see that the web includes a bowl-shaped sheet, and a flimsy sheet below that is supposed to resemble a doily. The web also has an extensive tangle of silk above a below the sheets. These act as knock-down threads to trap flying insects.

When an insect hits the tangle threads (usually invisible, but obvious here because of dew) they tumble down into the bowl. The spider is hanging under the bowl. She feels the vibrations of the insect and is waiting below when it hits the bowl. She lunges up through the silk of the bowl to bite the prey. Here is a close-up shot of Frontinella waiting for prey.

Another common linyphiid found in tall grass in southern Ohio is the beautiful scarlet sheetweaver (Florinda coccinea). The webs can be hard to spot, but are worth looking for because the spider is really spectacular, although small. Here is a photo of one in a web.

Here is Steve Buchanan’s illustration of this spider from my Common Spiders of North America book. You can see why it is worth looking for this gal.

illustration of scarlet sheetweaver (Florinda coccinea) by Steve Buchanan from Common Spiders of North America

My last example of a sheet web is from a very common Ohio spider, the hammock spider (Pityohyphantes costatus). This spider spends the winter as a sub-adult, so large webs like these can be found fairly early in the spring.

Space-filling webs–also referred to as either three-dimensional or cobwebs. Most of the spiders that build these webs are found among the threads, or just off to one side. The webs can fill a large space, or be a little tangle in a corner. Our most common spider, aptly named the common house spider (Parasteatoda tepidariorum; once known as Achaearanea tepidariorum) builds this type of web. Here is a fairly typical common house spider web in a window sill.

You can see quite a bit of “structure” in this web. Make no mistake, this tangle is not random. It was built to catch prey, and designed by the resident spider efficiently for that purpose. Among the structure visible here are a number of taut vertical silk lines attached to the window sill itself. These vertical lines are referred to as “gumfoot lines” because they have glue droplets near the bottom where they are attached. In fact, they are key to the function of this web. In addition to the glue drops, they have an intentional weakness at the point of attachment. When an insect or other small creature walks along and bumps one of these lines it gets stuck in the glue. As it struggles to break free, the weak attachment ruptures and the elastic silk line contracts. The glued victim is hauled up into the air as if by a reverse bungee cord. Now the spider has the advantage. She can approach and throw silk on the hapless insect that is hanging in space with no place to grab. Soon it is trussed up in silk and ready to be a meal. Below is another common house spider cobweb that has gathered plenty of dust.

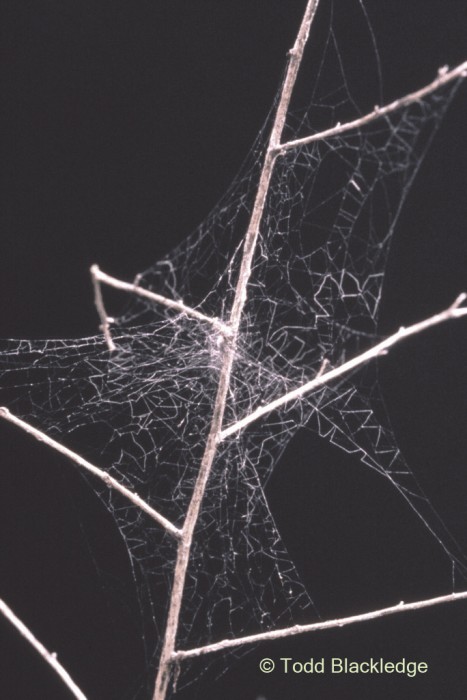

Some spiders build their space-filling webs at the tips of branches. This small cobweb weaver without a common name (Theridion differens) built her web in the fork of a branch.

Below is the last example of a space-filling type web. It is the web of a meshweaver (family Dictynidae). They are distinctive because they have a special type of silk, called cribellate. This is composed of dozens of extremely fine threads teased into a flocculent line. The cribellate strands are stretched zig-zag between support lines. Even though they do not have any glue, these webs are sticky because of the fine fluffy nature of the cribellate lines.