In a woods near you there may be an amazing little spider called Hyptiotes. This spider (and relatives in the same genus around the world) are famous for constructing a triangle-shaped web, hence their common name “triangle weaver.”

The web is unusual for many reasons but most folks look at it and see what appears to be a pie-slice out of an orb web. There are radial lines converging on a point, and there are parallel spaced silk lines forming a pattern that does look like part of a typical orb. But these webs are different. They have been built by a spider that uses cribellate silk, not glue-laden silk to entrap prey. The cribellate silk is sticky in a completely different way. It has tiny fluffy silk lines surrounding central lines. The fluff is so fine that when an insect or other potential prey brushes against it, they adhere to the hairs and spines on the prey in a way similar to the function of a Velcro © strip.

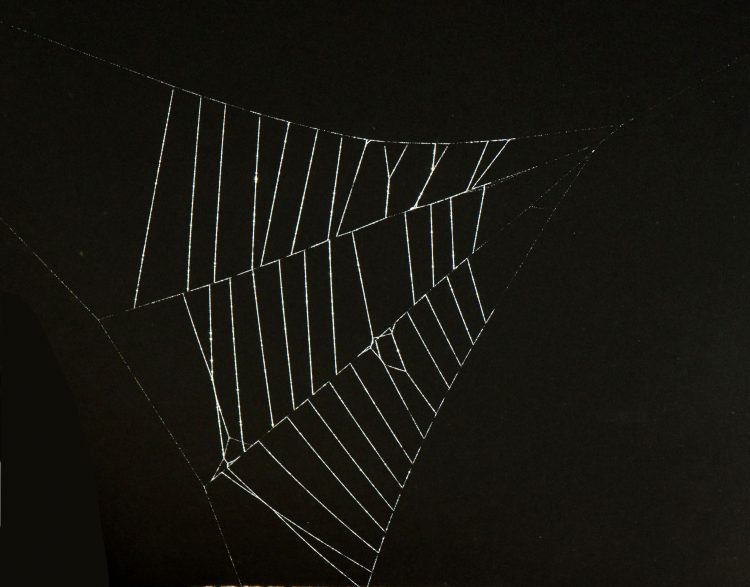

Here is a photo of the triangular sticky portion of a Hyptiotes web, made visible by a dark cardboard background after I misted it with water.

That isn’t the most amazing feature of the triangle weaver’s web. This tiny spider (they are only about the size of a grain of rice) holds the entire web structure under tension, pulling her line taut with her back legs and gathering the slack in a small ball of silk that lies on top of her legs. If a fly, or other potential prey, strikes the web and is caught in the sticky cribellar line, the spider rapidly releases the tension. This causes the spider to jerk forward as the web partly collapses. The collapsing web further entangles the prey. She may use this technique several times to effectively snare the victim.

Here is a close-up view of Hyptiotes as she is holding her web under tension, you can notice the little pile of slack silk line near her back legs. In this case there is also a small ball of slack near her front legs. I’ve added arrows to highlight these little bundles.

A couple of weeks ago I noticed that one Hyptiotes had built her snare between a thin dry twig I had laid across the arms of a lawn chair and the body of the chair. This is the first time I’ve found Hyptiotes in my yard, and also the first time I’ve ever seen one build a web away from a woods or forest.

This presented an opportunity too good to miss. I decided to take some close-up photos and also see if I might be able to shoot some video of her in action. The photos were much easier to get. Here are two that feature this amazing little spider.

Now for trying to shoot video. The capture rate for this little gal in my lawn chair was much too low for me to just set up and wait. I needed to “feed” her prey. So I captured a house fly and anesthetized the fly with CO2 to immobilize it. Then I dropped the fly into the web. I was thrilled when the fly actually “stuck” in the cribellate threads. This stimulated the Hyptiotes, she quickly released the tension in a jerk, then repeated it a couple of times. This collapsed the web on the fly as she moved in for her meal. Remember the spider is really small and positioned in the extreme upper right of the field-of-view at the beginning.

There are a few problems with this video, but it is the best one I’m managed to get so far. The web is very difficult to see through the viewfinder of the camera, so I didn’t aim perfectly so for a moment the spider-and-fly disappear at the bottom edge of the view. Eventually I noticed this and shifted the camera on the tripod to reveal the action.

You may have noticed that the “jerks” as she released the web, early in the video, are very fast. It turns out that Hyptiotes are now famous for their ability to harness the potential energy of the tense web very efficiently. A recent paper by Sarah Han and colleagues, she demonstrated that this spider employs what physicists call power amplification. Here is how they describe the action:

Both spider and web spring forward 2 to 3 cm with a peak acceleration of up to 772.85 m/s2 (Han, et al. 2019)

Other animals that employ elastic-energy storage and recoil usually have anatomical structures, like triggers or catches, associated with this behavior. Hyptiotes manages this feat with pure muscle power. Remarkably they hold the line under tension for hours at a time, waiting for the right moment to release the web and snare dinner.

After the capture, like any good uloborid, Hyptiotes wraps the prey, but does not bite. Members of the family Uloboridae lack venom, they don’t even retain venom glands. So they cannot subdue their prey that way. What they do is wrap the prey tightly in silk, then they engage in external digestion by spitting a mixture of digestive fluids onto the prey ball. This gradually dissolves the prey into a mush that they can suck in. Here is a photo of my resident Hyptiotes with the remains of prey that has been reduced to a wet ball of goo.

Hyptiotes with her meal, the wrapped prey is swathed in digestive fluids. It will eventually be completely liquified and ingested.

Read more about Hyptiotes power amplification:

S. I. Han, H. C. Astley, D. D. Maksuta, and T. A. Blackledge. 2019. External power amplification drives prey capture in a spider web. PNAS, vol 116 (24) June 11, 2019. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1821419116

Wow! Very exciting!!

I just took a picture of a Halloween spider in Ct. today. It’s the most beautiful thing to see because I just love all of them. Thanks for all you do.

Michael, I approved your comment, but it actually belongs on the halloween spider blog. I’m sure a WordPress expert could tell me how to move your comment to that blog, but perhaps it doesn’t really matter.

Thanks so much for taking the time to photograph and film your amazing triangle spider’s behavior! This was fascinating and educational for me and proves once again that there’s always something new to observe in the natural world!!