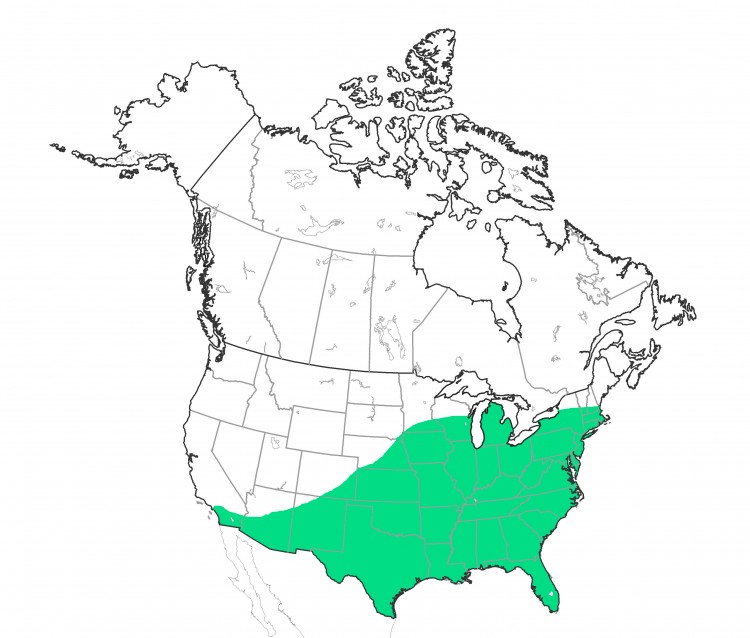

The Marbled Orbweaver (Araneus marmoreus) is one of the most common large orb weaving spiders in North America. It is particularly abundant in Ohio. Even so, many people here never notice them. I believe that this is because they live in wooded areas, typically come out only after dark, and hide in a retreat during the day.

This species is extremely variable in color and pattern. Here is Steve Buchanan’s painting of some color forms of the species from plate 9 in Common Spiders of North America:

The most common color forms encountered here in Ohio are the yellow and orange varieties. Like most large orbweavers, the Marbled Orbweaver lives less than one year. Young emerge from the egg case in the spring. At that time they are tiny and inconspicuous. By early summer they have grown to small juveniles (1/8 to 1/4 inch body length), and are typically cream or pale yellow with little pattern. By mid summer they are large and well marked. If you encounter one in its web at that time of year, they bear a conspicuous pattern on the abdomen.

This species builds a beautiful orb-shaped (circular) web low in a tree or herbaceous vegetation near the ground. Most individuals re-build their web every evening. Sometimes they replace only the sticky spiral portion. This difference probably depends upon how much the web is damaged by the previous night’s hunting activity. From the center of the web (the hub) there is a taut “signal line” that extends into the retreat. The spider often stays in the retreat with one or more legs touching the signal line, only emerging when a prey item becomes entangled in the web. She detects the presence of the prey via the signal line which transmits the vibrations made by the struggling prey. It only takes her a moment to rush out to the web, find the prey, and bite. The spider often bites insects on their underside. This ensures that the venom will paralyze the victim quickly because the central nerve cord of insects runs along the midline there.

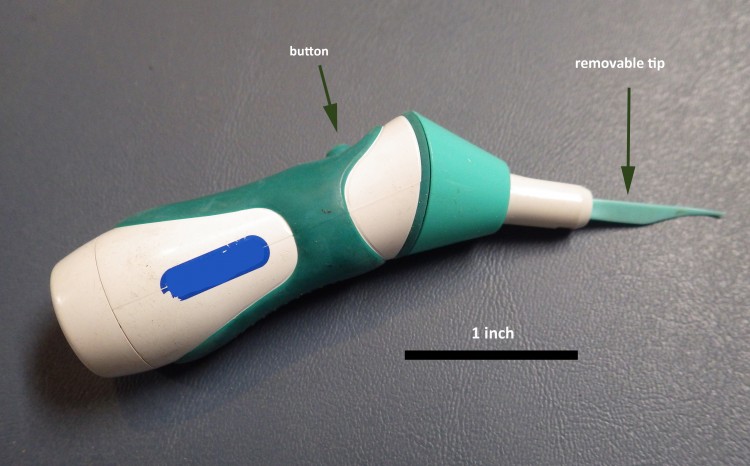

I often use a simple vibrator (inexpensive dental tool) to lure spiders out of their retreat. When she comes out and finds no prey item, she quickly retreats.

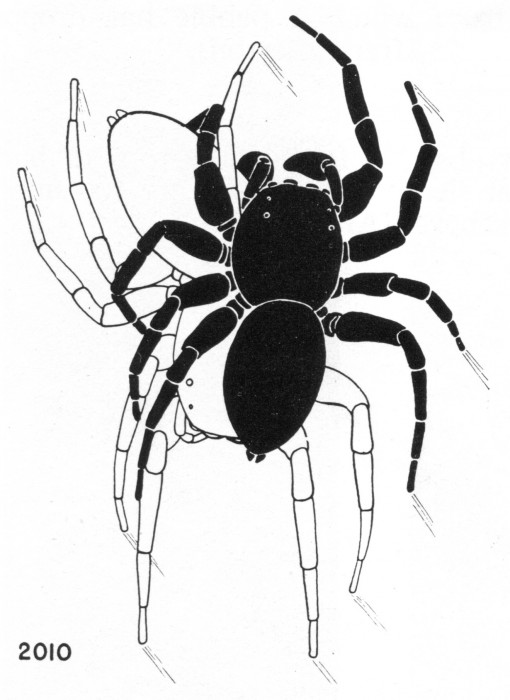

In the summer you may also encounter a male Marbled Orbweaver. These are leggy beasts, with a relatively small abdomen. After achieving maturity, the males spend their short lives searching for females. They quit building capture webs and wander through the vegetation, following pheromone scent trails to females.

For me one of the fun natural events in Ohio every October is the appearance of “Halloween Spiders.” These large, fat, bright orange spiders seem to appear on cue as the spooky holiday approaches. In fact, these are the orange color form of the Marbled Orbweaver. I’ve recently discovered that the very same individuals that have the typical yellow abdomen in summer, turn orange in October. This may correspond to the changing leaf colors. Many spiders, most famously the flower crab spiders, can change their color to match their background, and thus remain camouflaged. The odd thing in this case is that Marbled Orbweavers are often conspicuously colored, not camouflaged at all, as anyone can see from the other photos in this post.

These fat orange spiders are pregnant females, their abdomens swollen with hundreds of eggs. Sometimes people find them walking on the ground, driveway, or patio deck. In late October, a grape-sized bright orange spider conjures up the image of a miniature pumpkin, and I have received many excited email messages about them over the years. Fortunately I can re-assure the correspondent that this is merely a harmless female spider searching for a good place to lay her eggs. Perhaps this is the reason for the camo color, because walking through the fallen leaves in the daytime is a real departure from their summer reclusive behavior. These females will die soon after laying their eggs, often coincident with the first hard frosts of autumn.