One of our strangest-looking spiders is Ocrepeira, the asterisk spider. She has an amazing camouflaged color pattern complete with little lumps on her abdomen. She is actually related to our more common orb-weaving spiders, but has a very unusual web.

There are 68 species in the genus Ocrepeira (sometimes known as Wixia). All but three of these are found in the tropics (Central or South America). Of the three northern species, two are known from Ohio. During the Ohio Spider Survey (1994-2014) ten individuals of Ocrepeira ectypa were found, two of Ocrepeira georgia, and four immatures that could not be determined. So this spider isn’t encountered very often. One reason is that they really do an excellent job of hiding, they look just like a broken branch or bud on the stem of a shrub or tree.

Ocrepeira resting on a twig in Adams County, Ohio

Ocrepeira posed front view

Ocrepeira posed side view

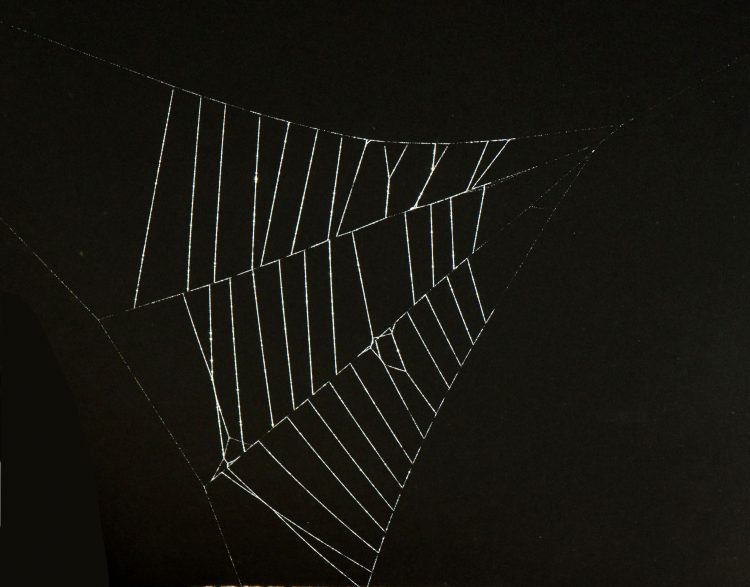

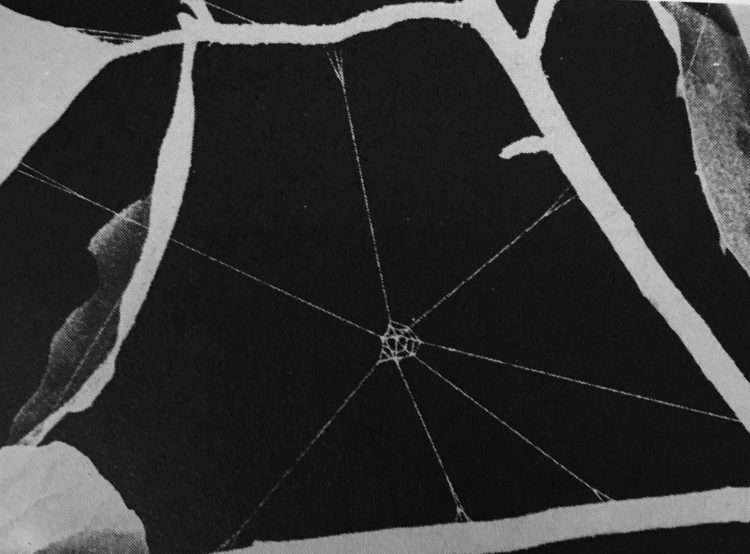

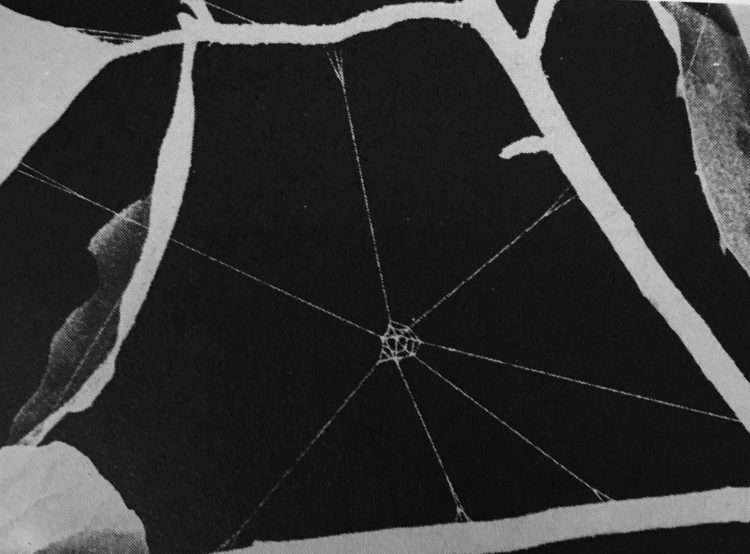

This spider is known as the “asterisk spider” because of its web. The web consists of an orb like array of radial threads connected to a loose hub where the spider sits when she is hunting. Because the web does not contain any sticky silk, and because the radial threads spread from the central hub in a star-like pattern, the web is thought to resemble an asterisk mark (*).

The Asterisk Web of Ocrepeira (photo from Stowe, 1986)

Ocrepeira next to her asterisk web

Ocrepeira at the hub of her asterisk

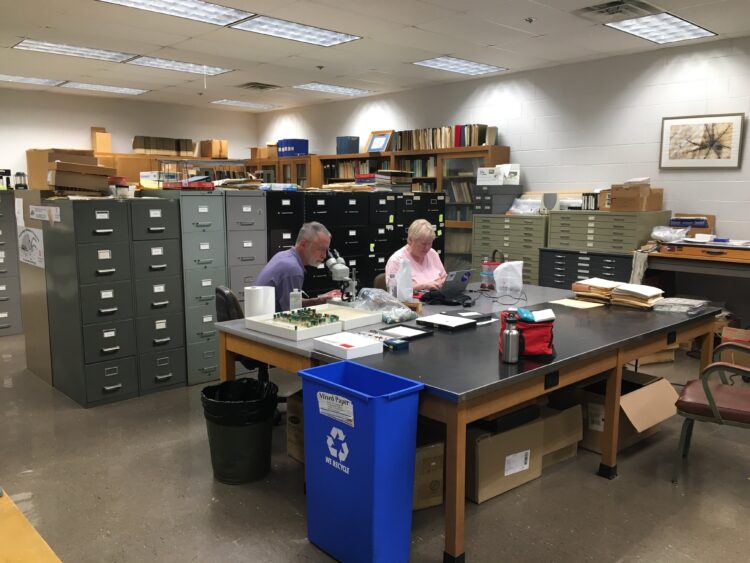

In his 1976 monograph, Herb Levi describes the natural history of these spiders thus:

“All three species are rarely collected but are found in wasp nests (Levi, 1973). They probably make their unknown orbs in trees and rest at daytime appressed to twigs.”

Now we know that Levi was partly correct, the web is built at night, but it is not a complete orb. The first accurate description of the web of this species was made by Mark Stowe (1978). Mark mentions that it was extremely difficult to observe the construction of the web which is built by the spider very quickly at dusk. When hunting the spider sits at the hub of the web and waits. Prey are detected as they walk on the branches supporting the web, or bumping into one or more of the silk threads. The spider then rushes to the branch and captures the walking prey on the branch. Stowe describes this sequence in his 1978 paper.

“Usually the spider first ties down the prey by rapidly circling the branch and the prey while laying down swathing silk. This prevents the prey from escaping and facilitates subsequent biting. When the venom takes effect, they prey is freed from the branch by biting the restraining threads and after more wrapping the prey is eaten at the capture site or at the hub.”

When Laura Hughes told me about finding a female Ocrepeira she had located in Adams county, we agreed to meet there and observe the spider. We were hoping to see her hunting technique. Thanks to Laura’s great notes and memory we were able to re-locate the spider. When we arrived at the small Eastern Redbud tree at 7:30 pm on 25 September, 2019, she had already built her web.

Ocrepeira in her web in Adams County, Ohio

The weather in early September last year had been very dry, and there were few insects or spiders active in the area. We had hoped to capture some local insects as potential prey and offer them to the spider. Unfortunately, we couldn’t really find suitable prey. Most of the potential prey that we caught refused to walk on the branches. We did get one grasshopper nymph to walk near the spider, but it was evidently too large. The spider did not take the bait. She eventually retreated to the branch and assumed her cryptic posture.

Ocrepeira ignoring a grasshopper (above spider on branch)

So our quest to observe and photograph the hunting technique in the wild was foiled. I captured the spider to see if I could get her to hunt in captivity. I set up a small branch from one of our redbud trees that had about the same sized branches and an arrangement angles similar to the situation were she was captured. To minimize disturbance she was housed in a windowless room at my home. I put a light on a timer coordinated with the light/dark cycle. At night the room was lighted with a dim red light (so I could observe and navigate). Past work with spiders has indicated that many species cannot see red light, and will continue their nocturnal behavior without disturbance. Remarkably, she was quite cooperative and built her asterisk web on her new home.

captive Ocrepeira in her web (flash photo)

I tried several potential prey, including handsome trig (a common bush cricket), moths, small beetles, small crickets, mealworm beetles, and small cockroaches. She did not take the bait. I continued to offer prey each night. The spider built a web every evening then removed it and retreated to a resting position in the morning. All my attempts to get her to feed, failed.

Ocrepeira on branch

I continued the next few nights without success, then on the 2nd of October, she produced an egg sac. Maybe that is why she wasn’t feeding? I don’t really know. But the very next day I fed her a small walkingstick, and she took it. Everything happened so fast, it was very difficult to see in the dim red light. The spider whipped around the walkingstick in an instant, presumably trailing a silk line to tie it down. Then she moved in and bit near the end of the abdomen.

Ocrepeira bites walkingstick prey (flash photo)

I never saw her use “swathing” silk the way I had expected from Mark Stowe’s description.

After the Ocrepeira began feeding on the walkingstick, I left her in peace. When I checked after the lights were back on in the morning, she was in her typical resting position and there were no remains of the walkingstick.

It was getting late in the season, and I was having difficulty finding prey for the spider. The most abundant insects were large craneflies. They seemed to be good potential prey, and she did take them. Unfortunately it was extremely difficult to photograph captures. Here is one photo of the remains of her cranefly prey, wrapped with silk to the branch near where she hunted. Later in the month she died.

asterisk spider prey; wrapped craneflies

We don’t know how rare Ocrepeira is, there are so few records for Ohio, but it is also a very cryptic spider. It is possible that they are far more common than these records indicate. The records are scattered across the southern half of the state. In Herb Levi’s 1976 monograph there were none from Ohio, the records were scattered along the Atlantic coast from Massachusetts to Florida, with additional records in Georgia, Missouri and Arkansas. Given this paucity of information, it seemed best to return the egg mass laid in captivity back to the location where the female had been found. So Laura returned it to the original site in Adams county.

Ocrepeira egg case in folded redbud leaf

So I’m still hoping to witness an Ocrepeira natural prey capture event, but that will need to wait for another opportunity.

Levi, H.W. 1976. The Orb-weaver General Verrucosa, Acanthepeira, Wagneriana, Acacesia, Wixia, Scoloderus and Alpaida North of Mexico (Araneae: Araneidae). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 147(8): 378-384.

Stowe, M.K. 1978. Observations of two nocturnal orbweavers that build specialized webs: Scoloderus cordatus and Wixia ectypa (Araneae: Araneidae). J. Arachnol. 6: 141-146.

Stowe, M.K. 1986. Prey Specialization in the Araneidae. pp 101-131 IN Shear, W.A. (editor) Spiders Webs, Behavior, and Evolution. Stanford University Press, Stanford CA.