For the past few summers I’ve taught a Spider Biology course (EEOB 5210) at The Ohio State University’s F.T. Stone Laboratory on Gibraltar Island in Lake Erie. The course will be offered again this summer (2016), from July 31 through August 6. This is a regular Ohio State University course, providing two semester hours of credit for upper division or graduate students. With permission, the course can also be taken as a non-credit workshop for those not currently enrolled at OSU.

Gibraltar Island, Lake Erie, Ohio

main Stone Laboratory building

Now is the time to investigate signing up for the course. One reason is that many students can benefit from scholarships that provide partial support for the course costs. These scholarships are supported by the Friends of the Stone Laboratory. The deadline for a scholarship application this year is March 3, 2016.

welcome sign, F.T. Stone Laboratory

This is an intensive, residential, one week course that introduces spiders and spider research to college students. Past classes have included undergraduates, graduate students, as well as teachers and other interested naturalists. We all live and breathe spiders for seven days, beginning, after introductions, with an evening spider walk around the grounds of the laboratory on Gibraltar Island on Sunday night. Most of the students have little experience with spiders; but some have been keen spider enthusiasts, even a few academic arachnologists.

Larinioides patagiatus female hanging from a web on the outside of the laboratory building

Observing some species of spiders requires a bit of encouragement. One simple method is to gently wiggle a brush in the silk “signal” lines running out from the retreat. For viewing the tubeweb weaver (Ariadna bicolor) this technique can be very successful. Below you can see her attacking the brush. Eventually we managed to lure one completely out of her tube.

luring a tubweb spider (Ariadna bicolor) from her tube retreat

another Ariadna leaves her tube and bites the brush

Others are found out wandering on the walls of the buildings or other structures. These include the day-active jumping spiders. Here are a couple of photos of the Zebra Jumper, a common harmless jumper found on Gibraltar Island.

zebra jumper (Salticus scenicus) female

zebra jumper (Salticus scenicus) female

Each day begins with morning lectures followed by afternoon laboratory and field work. During the evenings early in the week, we often convene to search for nocturnal spiders around the island. As the week progresses the students begin to focus on their individual research projects, and much of this work is done in the late afternoon and into the night. Of course, many spiders are nocturnal, so this necessitates field work at that time of day.

Monday’s first afternoon laboratory is an intensive introduction to spider anatomy with way-too-many unfamiliar anatomical terms. By the end of the week, the students all eventually master these, and are conversing in phrases like “median ocular area” and “retromarginal teeth” or “long posterior spinnerets.”

students working in the lab

Christopher Klemm working with a spider identification key

The course is an exploration of the biology of spiders (Order Araneae), but I try to create a relaxed informal environment for learning. Topics include functional anatomy, senses and perception, behavior, webs and web-building, identification, classification and relationships, field techniques, and ecology.

Michael Chips installs a pitfall trap as the class looks on

Sarah Rose checking a pitfall trap

collecting spiders from a beating sheet

Lectures are profusely illustrated with photos and videos of spiders and spider behavior. There is a tradition of an evening “movie night” with silly commercial hits such as the John Goodman classic: Arachnophobia (1990). Even watching this movie can be a spider-nerd challenge. For example: there several different families of spiders represented as one species in the film. It is difficult to identify them from their brief furtive appearance on the big screen.

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin

Spider identification is a tricky skill to master. We begin in the field “spidering” similar to beginning birding, focus on the large and conspicuous species. The big orbweavers, which are so very common on Gibraltar, such as the Furrow Orbweaver (Larinioides cornutus) and its relative Larinioides patagiatus are among the first ones we find. These big spiders are the “Great Blue Herons” of arachnology.

furrow orbweaver (Larinioides cornutus) female

furrow orbweaver (Larinioides cornutus) female

furrow orbweaver (Larinioides cornutus) male searching for a female

We usually see plenty of the abundant introduced “House Sparrow” of spiders, Common House Spider (Parasteatoda tepidariorum).

common house spider (Parasteatoda tepidariorum) with a bug prey item in the corner of the lab

Students quickly learn that color and pattern aren’t often useful for spider ID; shape & behavior are better clues. With practice, subtle features like eye-arrangement and spinneret structure are recognizable. For some groups, a quick look at the “face” can be distinctive.

wolf spider face and jumping spider face

Field work in this course includes work around Gibraltar island, as well as a field trip to sites on South Bass Island. We observe, and sometimes collect spiders on these trips. Some of the specimens are incorporated into the individual student collections, others are used in individual projects.

Agelenopsis, the grass spider poses in the open after being lured out of her retreat

One of the first lessons in a course such as this one is that “daddy-long-legs” aren’t spiders at all. They are sort of cousins to spiders, members of another group, the harvestman (Order Opiliones). Being arachnids, they share many features with spiders, for example they have four pairs of legs.

Harvestman, not a spider, but a related arachnid in the Order Opiliones

Along the cobbles of the shoreline in the evenings it is often relatively easy to find larger wolf spiders, such as this Pardosa.

wolf spider (Pardosa lapidicina)

immature hammock spider (Pityohyphantes costatus) with a midge prey

The spider below looks similar, but students learn to use a magnifying glass to examine distinctive features such as the high clypeus of Pityohyphantes compared to the low one of Tetragnatha.

Tetragnatha laboriosa female

Some spiders do well in the laboratory and make good captive study subjects. One example is the fishing spider (Dolomedes tenebrosus), below in the field, and then a close up of the same gal feasting on a mayfly in captivity.

fishing spider (Dolomedes tenebrosus)

captive fishing spider (Dolomedes tenebrosus) eating a mayfly

Some of our finds are common introduced species, such as this female Enoplognatha ovata with her large egg case.

Enoplognatha ovata with her egg case

Others are quite rare, like this female running crab spider (Philodromus imbecillus) which represented the third locality record for the state when we found it on the field trip along the Jane Coates Wildflower trail. This site is maintained by the Lake Erie Islands Conservancy.

Philodromus imbecillus female guarding an egg case, also with previous cases (now empty)

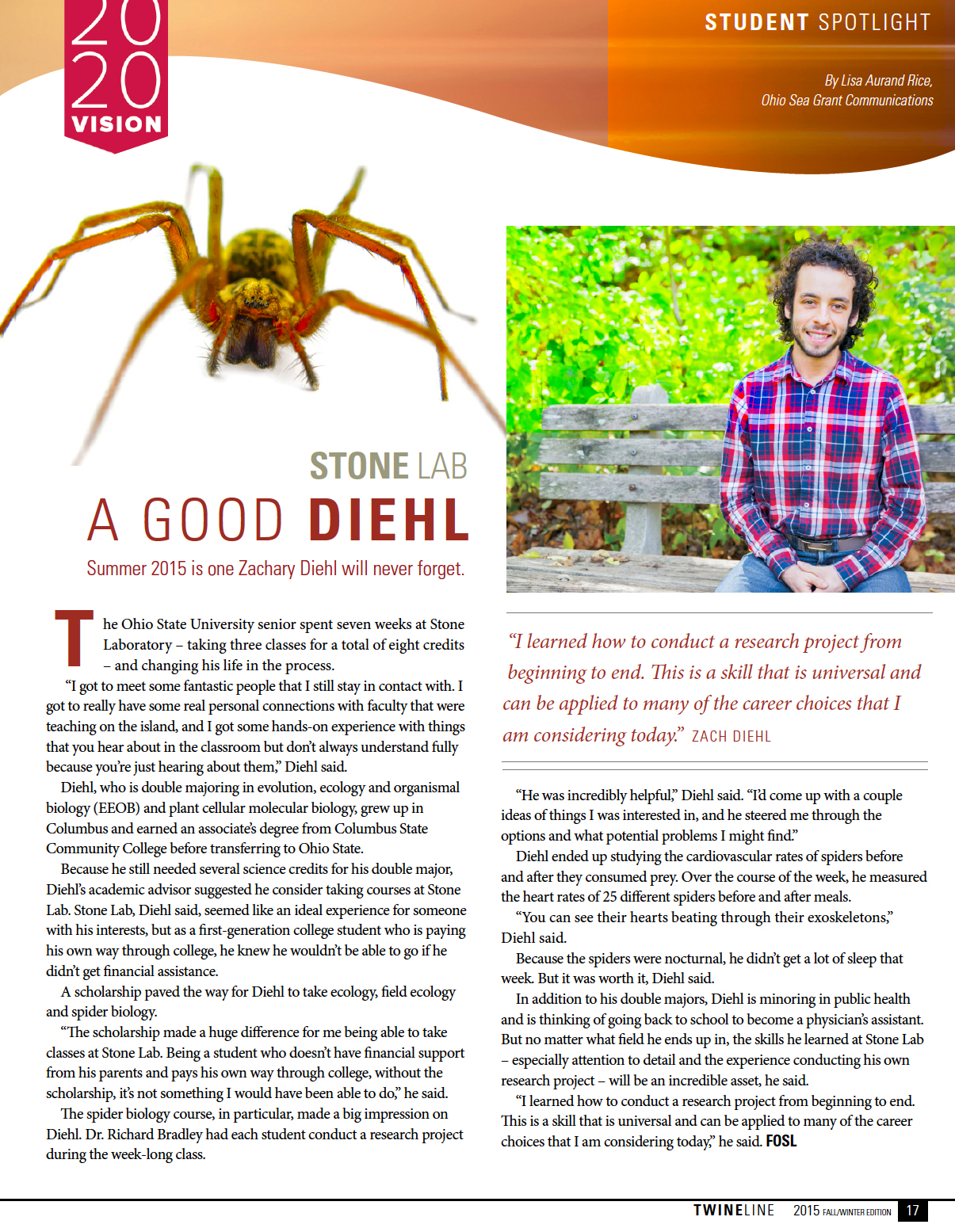

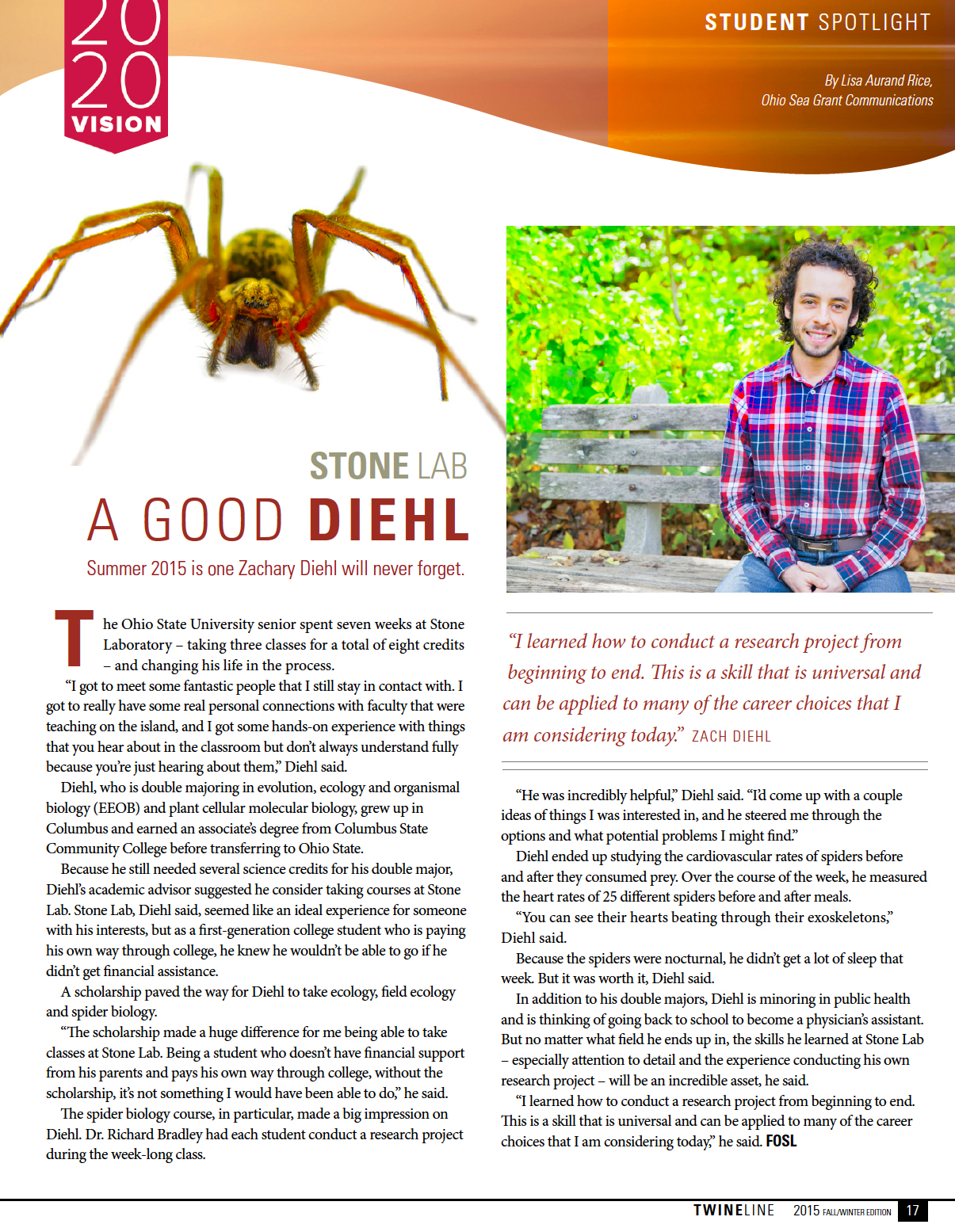

One key component of the course are the individual projects. Each student chooses a topic of interest and investigates it in some detail. They collect data and conduct analysis. At the end of the course each student summarizes their results in a brief presentation to the class. For many students, the individual project is the highlight of the course. It is a chance for them to delve deeply into a particular topic suited to their personal interests. Past topics have included census work around windows on the research building, courtship behavior of jumping spiders, and variation in web structure. One of last year’s students, Zachary Diehl focused on spider heart rates.

from Twineline Fall/Winter 2015 p 17

The perennial stars of the course are the often charismatic jumping spiders (family Salticidae). They are the “Blue Jays” of arachnology, conspicuous, colorful, active, and overall fascinating predators.

Sara Klips observing jumping spider behavior as part of her research project

jumping spider (Phidippus putnami) female

jumping spider (Colonus sylvanus) female

jumping spider (Phidippus clarus) female

dimorphic jumper (Maevia inclemens) female

By the end of the week students have achieved the goals of this course and will have:

• learned to appreciate the diversity and relationships among spiders

• learned the functional anatomy of spiders

• become proficient in advanced spider identification

• learned to conduct field study of spiders using standard techniques

• learned to recognize and understand common spider behaviors

• experienced the micro and macro habitat preferences of spiders

• designed and conducted a small research project

Here are a few “group portraits” of our last few Spider Biology courses.

class group portraits, clockwise from the upper left, 2007, 2012, 2013, 2015

Naturally, the impact of any summer course at the F.T. Stone Laboratory on Gibraltar is due to the unique learning atmosphere there. The small classes and intense format mix to create a very special experience for all involved. It doesn’t hurt that the scenery is spectacular.

sunset viewed from Gibraltar Island

For more details about this course consult the Stone Laboratory course information page. Anyone with a specific question about this course is welcome to contact me directly.