It is that time of year again, I’m starting to receive email queries about large brown spiders in webs. Typical questions ask about identification and whether or not the spider in question is “dangerous.” The messages sometimes include helpful photographs, often taken with mobile phones. These snapshots are usually good enough that I can recognize the spider as Neoscona crucifera (aka arboreal orbweaver or variable orbweaver).

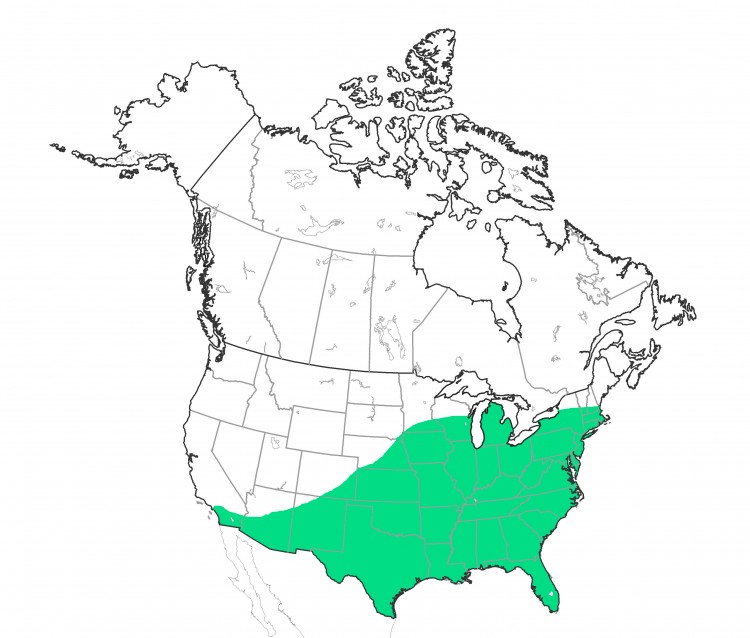

This species is interesting for a number of reasons. It seems to have adapted well to human-altered habitats. It is common at the edges of woods, orchards, suburban yards and even building webs directly on houses and other buildings. This species is common, even abundant in the east, and has recently expanded its range and abundance in the south and west.

The webs of this spider are often quite large, with a frame of 3-5 feet and an orb with a diameter between 1 and 1.5 feet. The webs may be built near windows or other light sources. I suspect that they build in such situations because of the abundance of potential prey insects attracted to lights at night. During late summer and autumn search for these spiders building their webs just after dusk. If you time it just right, you can catch them in the act. The amazing construction dance of a large heavy-bodied orbweaver is always a wonder to behold. Pay attention to the leg movements, that is how she uses her body dimensions to gauge the spacing of the spiral sticky strands, and of course the web becomes larger as she grows. After she is done, she will typically hang, head down, at the hub or center of the web for most of the night. Typical prey are large moths, beetles, and other night-flying insects. Sometimes the spider will remain in the web after sunrise.

Like all of the orbweavers found in North America, Neoscona crucifera is considered harmless to humans and pets. They are shy spiders and will either rapidly retreat, or perhaps drop from their web if disturbed. In my experience they do not bite humans. Like most spiders, they are venomous, but they employ their venom against insect prey.

One dramatic feature of the members of the orbweaver group (Family Araneidae) is the pattern on the belly (ventral side) of the abdomen. Most of them have a central black spot, usually nearly rectangular. At each corner of the black area are a series of pale (white, cream, yellow) spots. These spots can be shaped like a comma, or nearly round. The pattern of a black patch with such conspicuous spots is often mentioned by people when they see this spider for the first time. Sadly, they are not too useful in identification because some variant or another occurs in many species. For example, each of the four members of the genus Neoscona in Ohio include this feature.

Immature individuals of this spider emerge in the late spring, but they don’t become large enough for most people to spot until summer. By late summer they are hard to miss. The individuals that are most often noticed are females, which can be large. Some have a body length of about 20mm (3/4 inch) with a leg span of 1.5 to 2 inches. One of the most remarkable things about these spiders is how extremely variable they are. Some are plain, with a faint pattern on the abdomen, or no pattern at all. Others can show a dramatic cross-shaped mark on the abdomen, with or without a series of dark markings. Such variation doesn’t seem to be geographic, instead it is polymorphism that can sometimes be observed among several individuals in one locality. In addition to variation in pattern, the base color varies from orange, through reddish brown to a plain brown or tan.

The femora (large segments of the legs nearest the body) are usually orange or red in color. This can be seen when the spider has its legs completely spread, and may not show if the spider is in its defensive crouch.

The males can also be variable in color and pattern. They typically have a smaller body than the females, with proportionately longer legs. After reaching maturity, the males abandon their webs and wander in search of females. Perhaps because of their smaller, slender body, or leggy look, the spines on their bodies seem more prominent. These wandering males may accidentally enter houses. I have records of wandering adult males here in Ohio between 11 August and 11 September.

By the late autumn, the females have mated and are fat with eggs. They will construct one or more silken egg cases containing hundreds of eggs. These eggs survive through the winter and emerge once the weather becomes consistently warm in late spring. My records of adult females in Ohio extend from 15 June through 2 December. Most will perish with the first hard frosts in October and November.

You can find more information (p. 99) and illustrations of this species (Plate 15), and its relatives in my Common Spiders of North America.

Rich; What an excellent site, keep up the good work. In the past few years we have learned a lot about the spiders in our yard and the surrounding ares thanks to you. Bob

Yes eggsellent

Wow, thank you for your very descriptive page on the “Orbweaver”. I just had to know what type this was spinning a web right in the entrance area door to my shop in central Ohio. Makes me appreciate Gods creation even more now that I have learned about it. Thank You! David

Thank you for your articles!

Neoscona crucifera is typically one of the most abundant spiders in my rural, southernmost NJ yard, but this year they were very scarce. I’m blaming it on the dragonflies who took up residence around my dragonfly pond–I watched a Great Blue Skimmer routinely hunting any spider that drifted or dropped by within several feet of his perch. The Argiopes were missing, as well.

Your very plain N. crucifera is puzzling to me–I always see individuals with fairly strong markings. Did you know t look amazing under UV light? Links are to my photos on Instagram.

UV-lit photo… https://instagram.com/p/Bm7VWSPBsjT/

And I found a *pink* presumed Neoscona this fall! Identification (if possible from photo) would be appreciated, thank you.

PINK orbweaver… https://instagram.com/p/Bn-NOq7APf9/

I did NOT know that. I’ve found that a number of spiders do look remarkable under UV illumination. I need to get out next year and look for Neoscona, which are typically very common here too, but like you I saw fewer in 2018. The second photo looks to be Neoscona arabesca, and she is a beautiful one! I do think I’ve seen pinkish ones, as well as orange sometimes… “usually brown” doesn’t do them justice, they can be very colorful.

My question is whole KING OF THE WEB when it comes to dominance. New title male false black widow spider vs male orchard web weaver.

I’m unsure if your question includes misspellings? maybe you mean “who” instead of “whole”? Those two wouldn’t likely encounter each other, and typically any male spider is more interested in finding a mate than defending a web. So I’m guessing these two would ignore each other. The “false black widow” is an ambiguous common name, but often refers to one of the spiders in the genus Steatoda, such as Steatoda grossa or Steatoda borealis. They build 3-dimensional or “tangle” webs. The orchard orbweaver builds an orb web with a minimal space-filling tangle above and/or below the orb which is usually tilted, but close to horizontal. So it is even less likely that these two types of spiders would encounter each other.

I have taken in an orbweaver that has lost three legs on her left side . She has made a web on my back door but it isn’t the best considering her legs. I was wondering if there was anything I could do for her to be more comfortable ? Also wondering what may have caused it ?

If she is an adult, she won’t molt again, so no chance to replace legs. Not much you can do. She likely lost legs in a struggle with large prey, or another spider. But it is also likely that she was injured by accident around a window or door without your realizing it. You could catch insects and try to hand feed her. I recently read an article about soaking freshly killed insects (flies, crickets) in a dilute honey solution and presenting the wet prey to her face and jaws. She will sense the moisture and may grab the prey and feed. It is tricky. Obviously she is going to be shy, also there are many unsuitable insects (distasteful). Moths are a good choice but hard to collect.

I have one behind my house right now and it’s so cool! The web is HUGE!! About feet!

I have recently started preserving spiderwebs for display. I have been using webs that I thought were abandoned. I noticed it is this type of spider making them when I saw her last night after dark. My question is does this spider use the same web over again or need to ingest it to make new ones? I do not wish to harm the spider when taking the web.

Elizabeth, you don’t need to worry. These orb-weaving spiders re-build their webs often. Usually they replace the sticky spiral every day, sometimes more than once. The webs get disturbed often, and this usually requires a re-build. They will ingest the remaining silk if it is clean, but the amount in one web is not a problem to produce fresh.

If I fed an orb weaver some Skittles from my tiny shrunken hands, do you think she could spin a web of fabulous, colorful proportions?

hmm…. silly but an interesting topic. Check my post “color shifts” from back in 2015 illustrating how spiders change color based on what they have eaten recently. Of course the silly part is getting them to eat colored sugar coated candies, not so likely 😉

Great information thank you! I found one of these late this evening about 6ft up in the air and off to the side of the path I was walking (thankfully). I tried to get a good picture of her but it was difficult. Fascinating web and spider, impressive really. Glad to know she’s not a threat to me.